As part of our work optimizing global shipping, we track and analyze data on every commercial ocean vessel in the world. Once we learned about the collision between the USS Fitzgerald and the MV ACX Crystal, our team began to explore this data to better understand what happened. This was especially important to us as several members of our team are US Navy veterans. Our hearts go out to the families and friends of the service members who were tragically killed in the collision.

What we found shows some behavior akin to a “hit and run”. We have shared our analysis below. We are hopeful that any insights we can offer can be of help to the review of this event, or prevent future ones like it from occurring.

How do we know where these ships were?

By now, you have likely seen analyses of the path of the MV ACX Crystal. How did people get this data?

The International Maritime Organization’s Convention for Safety of Life at Sea, requires all vessels with gross tonnage (GT) of 300 tons or more to employ automatic identification transceivers to broadcast position and avoid collisions. These transceivers broadcast at different rates depending on location (every few seconds while in congested areas like ports, every few minutes while out at sea). Ships not only use transceivers to broadcast their locations but also to see — and avoid — what is around them in congested areas.

We monitor the world’s commercial shipping via a global S-AIS (satellite-based AIS). We pair this data with other sources, and add our own analytics, machine intelligence and machine learning for deeper understanding (this data is the basis of what we used for our analysis). While we did not have data on the USS Fitzgerald, we were able to build a larger data picture by looking at data from several dozen commercial vessels we detected passing through the collision area at this time, (more on this below).

When was the collision? 1:30 AM or 2:20 AM local?

As of today, there are still conflicting reports as to when the collision occurred. Some reports say 1:30 AM local (16-June 1630 UTC). Others say 2:20 AM local (16-June 1720 UTC).We believe the collision occurred around 1:30 AM local. Here’s the playback of the data:

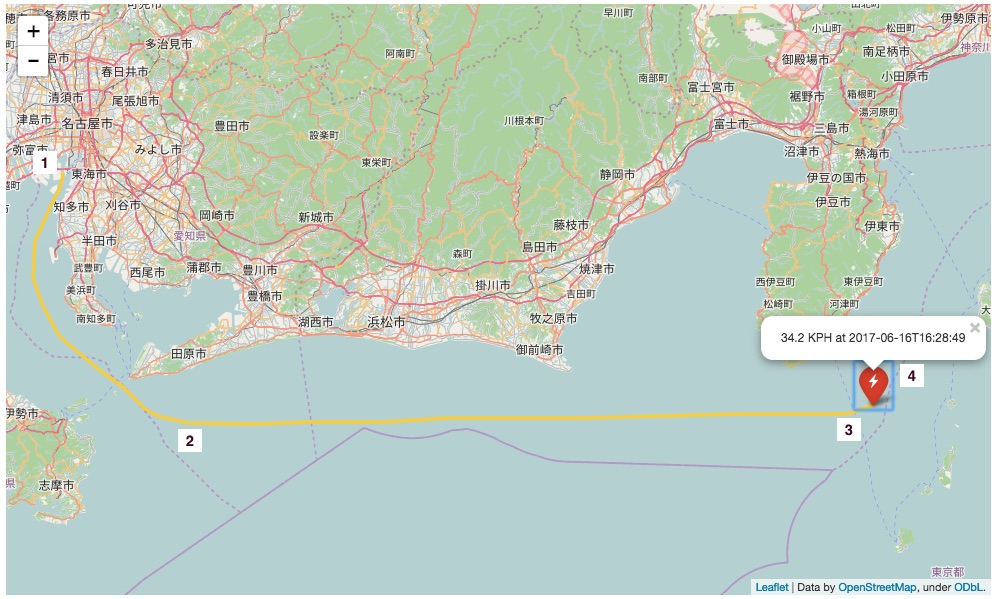

- MV ACX Crystal departs from Nagoya and travel along a standard shipping lane

- From 1110 through 1613 UTC, it was traveling virtually due East at an average speed of 33 kph (this is 80% of the MV ACX Crystal’s maximum speed)

- After 1613 UTC it shifted to a heading of East by Northeast

- It appears the collision occurred at 1628 UTC. At this time the MV ACX Crystal was moving at 34.2 kph (20 knots), at a heading of 68.0 degrees (East-by-Northeast) with a course over “ground” of 69.9 degrees, (that means there was a slight eastbound current).

Departure from Nagoya to the time of collision

Hit, pause, check, then leave

After this point, we start to see some anomalous behavior that looks like a “hit and run” (or “hit, pause, check, then leave”). Here is data, direct from the sensor:

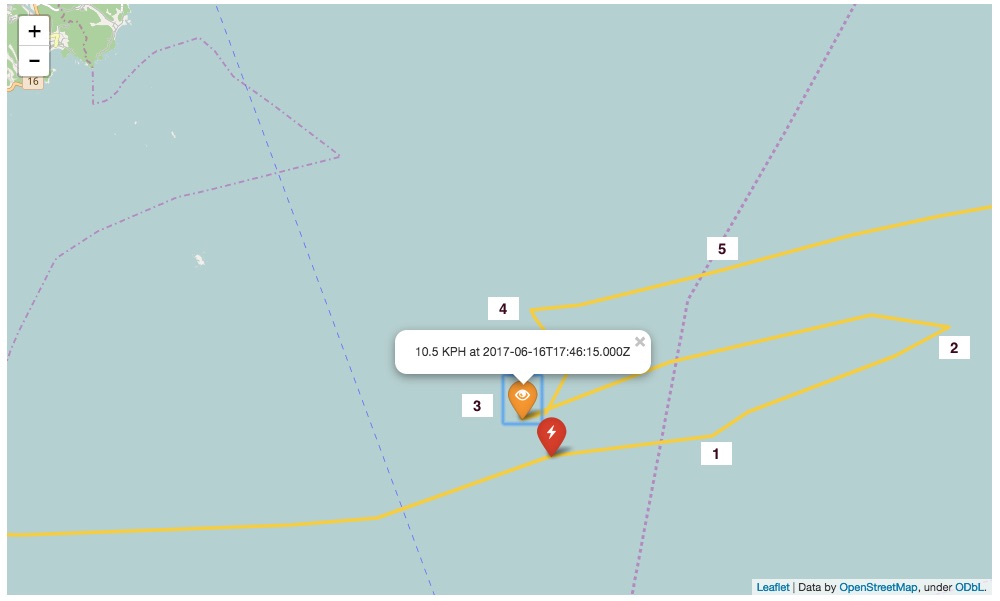

- After the collision, the MV ACX Crystal drops speed 20% to 28.5 kph and shifts slightly Eastward (55 degrees heading for the next 15 minutes)

- It returns to it’s original heading and slows another 20% to 20.7 kph. It continues on this heading until 1704 UTC, (36 minutes after the collision), where it then turns completely around, heading back towards the collision location

- After reaching a location near the collision location, it slows another 50% to 10.5 kph

- It then turns almost Due North at a crawl (3-6 kph) for 72 minutes

- The MV ACX Crystal then returns to nearly its original East-by-Northeast heading, accelerates to just over 35 kph–the same speed as before the collision

Multiple changes in speed and direction after the collision (including a return to the collision site).

Not Under Command?

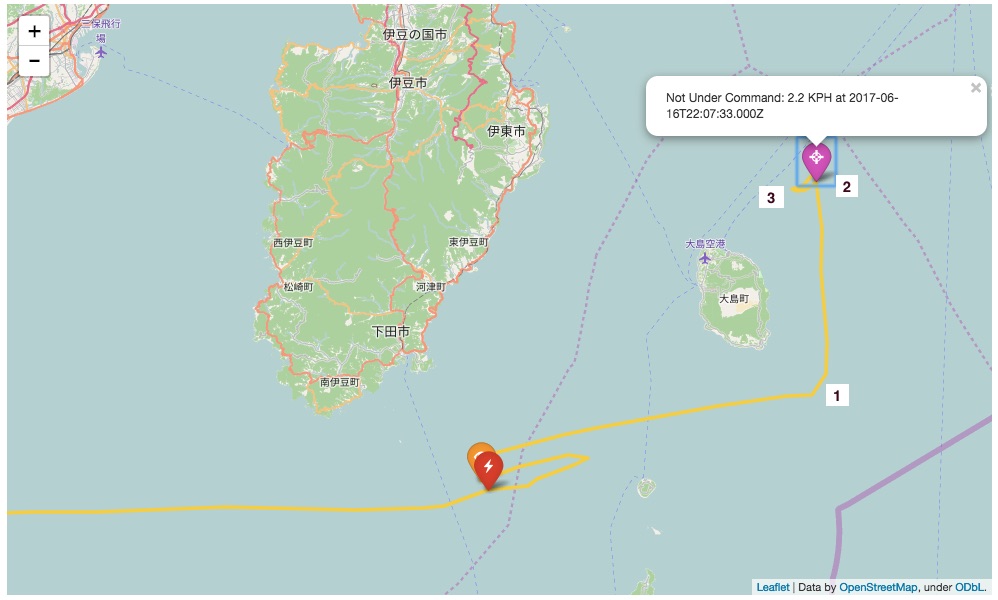

Up until this time, the MV ACX Crystal had been broadcasting its status of operation as normal (i.e, “Underway Using Engine”). Now things change.

- After 100 minutes, the MV ACX Crystal drops speed again, (this time also by one-third) and turns due North

- It continues North for 106 minutes, passing Izu Oshima Island, then switches to broadcasting the anomalous status of “Not Under Command”. This is not a normal condition. It would be very interesting to learn what was going on on the vessel during this time: boarding by the Japanese Coast Guard, damage inspection, something else?

- It then drops to 2 kph, detours Westward on a slow 3-hour-and-20-minute crawl, the returns to an Eastward course

Several hours after departing the collision area, the MV ACX Crystal changes its status to “Not Under Command”

Finally, at 0249 UTC (on 17-June) the MV ACX Crystal then switches back to broadcasting “normal” status of operation ( “Underway Using Engine”) and speeds back up to 24 kph. From this point, it continues onward to Tokyo without further incidents or abnormal changes in course or speed.

What else was going in the area on at this time?

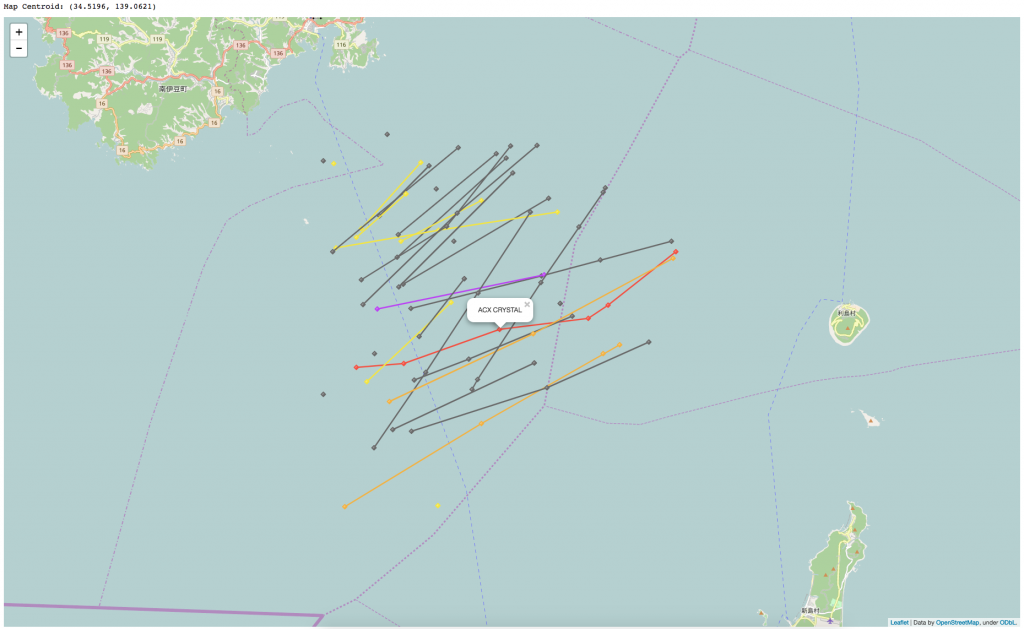

A lot of people are asking: how could a 154-meter destroyer not see a 220-meter container ship (or vice versa)? It is important to look at this in broad context of everything else that was going on at this time.

First, this was between 1 AM and 2 AM in the morning, at sea, at a moderate latitude. As there is no proximity to city lights, this means the ships were traveling in “pitch black” darkness. Second, this is a busy shipping lane — even in the middle of the night. We scanned for all the AIS-registered vessels that passed through the collision location (within one hour of the collision) and found over three dozen commercial vessels that criss-crossed paths:

- Eight were fuel tankers

- Two were ships rated for carrying Hazardous Category A cargo (the MV Maersk Evora and the MV Bay Chai Bridge)

- One was a passenger ferry (the MV Miho)

For all intent and purposes, this is a busy intersection off of Japan:

Commercial vessels traversing though the location of the collision, within and hour of the time of the collision. Gray lines indicate cargo ships, yellow lines indicate tankers (e.g., fuel tankers), orange lines indicate cargo ships that carry hazardous cargo, purple lines indicate commercial passenger vessels. The red line is the MV ACX Crystal route during this time window.

This does not take into account the many small fishing boats and pleasure craft in the area that were either under 300 GT which are not required to use AIS. It also does not account for ships that have tuned their transceivers to only receive AIS signals, (and not transmit locations), a common occurrence.

Those who have sailed in this part of the world will tell you that it is a very busy place.

Could any of these ships have collided with either the USS Fitzgerald or MV ACX Crystal?

So we found dozens of ships that were passing in close proximity to this collision. Could any of them had a collision?

We looked at this from two points of view:

- Could any of them collided with the MV ACX Crystal? We know where that was.

- Could any of them collided with the USS Fitzgerald? We only have a proxy of where that was.

The short answer is that things were quite safe. Two ships (the MV Golden Izumi and the MV Atlantic Eagle [3FOG8]) were virtually “ships passing in the night” with the MV ACX Crystal. But missed each other by 12-15 minutes. This reinforces the importance of using sensors and transponders for shipping safety.

What’s next

Today the Japanese authorities are getting the physical sensors from the MV ACX Crystal for “black box” analysis. Obviously, the many changes in course, speed and status between 1630-0300 UTC observed for the MV ACX Crystal are atypical in comparison to the average ship cruising “Underway Using Engine” at sea, along a shipping lane. It will be informative to learn what the investigators discover about what was happening during this 11-hour window. Hopefully their findings will make shipping safer for all.

For any questions about this analysis please contact us at info@savi.com